In the final stages of many terminal illnesses, care priorities tend to shift. Instead of ongoing curative measures, the focus often changes to palliative care for the relief of pain, symptoms, and emotional stress. Ensuring a loved one’s final months, weeks, or days are as good as they can be requires more than just a series of care choices. Anticipating the demands of end-of-life caregiving can help ease the journey from care and grief towards acceptance and healing.

In the final stages of many terminal illnesses, care priorities tend to shift. Instead of ongoing curative measures, the focus often changes to palliative care for the relief of pain, symptoms, and emotional stress. Ensuring a loved one’s final months, weeks, or days are as good as they can be requires more than just a series of care choices. Anticipating the demands of end-of-life caregiving can help ease the journey from care and grief towards acceptance and healing.

Understanding late-stage care

In the final stages of life-limiting illness, it can become evident that in spite of the best care, attention, and treatment, your loved one is approaching the end of his or her life. The patient’s care continues, although the focus shifts to making the patient as comfortable as possible. Depending on the nature of the illness and the patient’s circumstances, this final stage period may last from a matter of weeks or months to several years. During this time, palliative care measures can provide the patient with medication and treatments to control pain and other symptoms, such as constipation, nausea, or shortness of breath.

Even with years of experience, caregivers often find the last stages of life uniquely challenging. Simple acts of daily care are often combined with complex end-of-life decisions and painful feelings of bereavement. End-of-life caregiving requires support, available from a variety of sources such as home health agents, nursing home personnel, hospice providers, and palliative care physicians.

Identifying the need for end-of-life care

There isn’t a single specific point in an illness when end-of-life care begins; it very much depends on the individual. In the case of Alzheimer’s disease, the patient’s doctor likely provided you with information on stages in the diagnosis. These stages can provide general guidelines for understanding the progression of Alzheimer’s symptoms and planning appropriate care. For other life-limiting illnesses, the following are signs that you may want to talk to your loved one about palliative, rather than curative care options:

- The patient has made multiple trips to the emergency room, their condition has been stabilized, but the illness continues to progress significantly, affecting their quality of life

- They’ve been admitted to the hospital several times within the last year with the same or worsening symptoms

- They wish to remain at home, rather than spend time in the hospital

- They have decided to stop receiving treatments for their disease

Patient and caregiver needs in late-stage care

- Practical care and assistance. Perhaps your loved one can no longer talk, sit, walk, eat, or make sense of the world. Routine activities, including bathing, feeding, toileting, dressing, and turning may require total support and increased physical strength on the part of the caregiver. These tasks can be supported by personal care assistants, a hospice team, or physician-ordered nursing services.

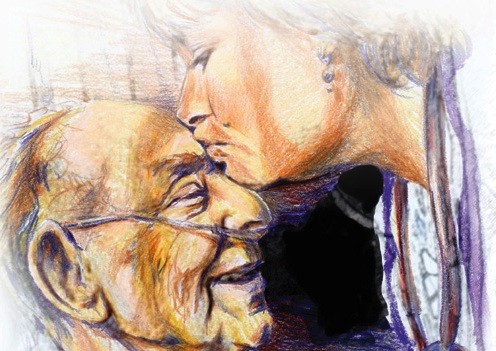

- Comfort and dignity. Even if the patient’s cognitive and memory functions are depleted, their capacity to feel frightened or at peace, loved or lonely, and sad or secure remains. Regardless of location—home, hospital, hospice facility—the most helpful interventions are those which ease discomfort and provide meaningful connections to family and loved ones.

- Respite Care. Respite care can give you and your family a break from the intensity of end-of-life caregiving. It may be simply a case of having a hospice volunteer sit with the patient for a few hours so you can meet friends for coffee or watch a movie, or it could involve the patient having a brief inpatient stay in a hospice facility.

- Grief support. Anticipating your loved one’s death can produce reactions from relief to sadness to feeling numb. Consulting bereavement specialists or spiritual advisors before your loved one’s death can help you and your family prepare for the coming loss.

End-of-life planning: decisions in late-stage care

When caregivers, family members, and loved ones are clear about the patient’s preferences for treatment in the final stages of life, they’re free to devote their energy to care and compassion. To ensure that everyone in the family understands the patient’s wishes, it’s important for anyone diagnosed with a life-limiting illness to discuss their feelings with loved ones before a medical crisis strikes.

- Prepare early. The end-of-life journey is eased considerably when conversations regarding placement, treatment, and end-of-life wishes are held as early as possible. Consider hospice and palliative care services, spiritual practices, and memorial traditions before they are needed.

- Seek financial and legal advice while your loved one can participate. Legal documents such as a living will, power of attorney, or advance directive can set forth a patient’s wishes for future health care so family members are all clear about his or her preferences.

- Focus on values. If your loved one did not prepare a living will or advance directive while competent to do so, act on what you know or feel his or her wishes are. Make a list of conversations and events that illustrate his or her views. To the extent possible, consider treatment, placement, and decisions about dying from the patient’s vantage point.

- Address family conflicts. Stress and grief resulting from a loved one’s deterioration can often create conflict between family members. If you are unable to agree on living arrangements, medical treatment, or end-of-life directives, ask a trained doctor, social worker, or hospice specialist for mediation assistance.

- Communicate with family members. Choose a primary decision maker who will manage information and coordinate family involvement and support. Even when families know their loved one’s wishes, implementing decisions for or against sustaining or life-prolonging treatments requires communication and coordination.

If children are involved, make efforts to include them. Children need honest, age-appropriate information about your loved one’s condition and any changes they perceive in you. They can be deeply affected by situations they don’t understand, and may benefit from drawing pictures or using puppets to simulate feelings, and hearing stories that explain events in terms they can grasp.

This article was originally written by,

Melissa Wayne, M.A., Lawrence Robinson and Jeanne Segal Ph.D.

Article Source:

http://www.helpguide.org/articles/caregiving/late-stage-and-end-of-life-care.htm