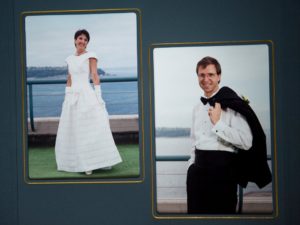

AFTER Mark Donham’s wife, Chris, fell under the spell of early-onset Alzheimer’s, he doubled down on his marriage vows. He quit his job as a well-paid sales representative in the printing industry and became his wife’s 24-hour caregiver: dressing her, doing laundry and scheduling social visits with friends. Faith, hope, and courage became his new mantra.

As Alzheimer’s slowly progressed and Chris became frailer, their lives narrowed. To explain their painful emotional journey to friends and family, Mr. Donham, who lives in Portland, Ore., began making videos and posting them on YouTube.

When his wife didn’t recognize him anymore, he said he felt as if his heart was ripping apart.

But Mr. Donham, still in his 40s, was being ripped apart in other ways, too. One day, he landed in the emergency room because he thought he was having a heart attack.

“It turned out to be stress and strain,” said Mr. Donham, who also joined an Alzheimer’s support group for men. “When you’re in the middle of caregiving, you don’t know what caring for yourself means.”

Looking back, Mr. Donham, now 54, says that caregiving, painful as it was, made him a “richer, deeper person.”

But five years after his wife’s death, it also has proved costly emotionally and financially. When he finally returned to the workforce, Mr. Donham took a pay cut and began commuting to Los Angeles. Despite having long-term care insurance, Mr. Donham spent about one-third of his carefully built retirement savings while caring for his wife.

Though caregiving can be a profound and moving journey, caregivers’ needs are often overlooked. The health care system is mainly focused on patients; caregivers who are slowly burning out can slip by unnoticed until it is too late.

“We’re seeing that caregiving burnout is more prevalent,” said Anne Tinyo, national manager of life management services at Wells Fargo Private Bank. “And it’s happening over a longer period of time.” Caregivers, she added, may even die before their loved ones.

Researchers have found that the human immune system can be weakened by stress and strain for up to three years after caregiving ends. As a result, caregivers can be more prone to having serious illnesses. Yet they rarely complain.

“Caregivers think that it’s shameful or wrong to ask for help,” said Mindi Golden, associate professor in communication studies at San Francisco State University. “But I’ve seen many people with physical injuries, such as rotator cuffs that were damaged while helping someone.”

The strains on caregivers have become more widely recognized lately and new efforts to help them are emerging. The National Alliance for Caregiving lists various resources on its website, including research on the impact of caregiving. Sites like Caring.com and the Family Caregiver Alliance offer online support groups.

The Alzheimer’s Association also offers many services, including online communities, nationwide support groups, and a 24-hour helpline.

Adult day care centers can offer some respite for caregivers. The Insight Memory Care Center in Virginia, which offers day care for people with Alzheimer’s, began offering caregiver cruises last year. They let caregivers enjoy a vacation to the Caribbean without leaving their loved ones behind.

Men, who generally have smaller networks of friends than women, are at even greater risk. “They are less likely to maintain relationships and seek help,” said Zaldy Tan, medical director of the UCLA Alzheimer’s and Dementia Care Program. “They’re less prepared for the caregiving role. So they have a higher burden and burnout rate.”

After hearing many people’s caregiving stories, Patti Davis, daughter of President Ronald Reagan, started a twice-a-week support group called Beyond Alzheimer’s five years ago. Everyone who enters the group, now based in Santa Monica, Calif., has some level of burnout, Ms. Davis said.

“People take on too much,” she said. “And so the stress becomes normal to them. The immune system is steadily eroded.” Many caregivers feel more comfortable talking about the Alzheimer’s disease rather than about themselves. “But they’re patients, too,” she said.

The symptoms of burnout can be hard for outsiders and the caregivers themselves to recognize. They include weight gain or loss, choppy sleep patterns, daily habits that get whittled away — and clinical depression.

Mr. Donham ended up recharging his system by taking a two-year trip to 26 countries on his BMW motorcycle.

“Take care of yourself,” he counseled. “Have a plan. Get involved in support groups. And know what help you’ll need, like mowing the lawn.”

Perhaps the best antidote to burnout, many experts say, is building a team, rather than handling everything yourself.

Mauny Kaseburg used the teamwork approach when caring for her dying parents. They didn’t want to leave their longstanding, custom-made home in the state of Washington. So Ms. Kaseburg assembled a family team that included her sister, niece, and daughter, who took turns caring for her parents. She became the team captain.

“It takes a village to help people die with dignity,” said Ms. Kaseburg, who lives on Mercer Island, east of Seattle, with her husband. “And if you’re lucky, it’s the village of family.”

She knew from the beginning that she didn’t want to become a “sacrificial lamb.”

The best family teamwork involves meeting, talking and sharing responsibility, Ms. Tinyo said. One team member, for example, can handle medical appointments, another might be good at preparing meals. “Have weekly phone calls if you’re in crisis,” she said.

Kristin Baird also used the teamwork approach when caring for her mother, who had cancer and needed round-the-clock professional care. Ms. Baird visited nearly every day to help out. Her husband took on household chores. Two daughters who lived nearby pitched in.

Even so, she struggled constantly to balance all the caregiving responsibilities.

Ms. Baird, who is president of the consulting firm Baird Group, scrambled to keep her 18-employee business cranking. She logged onto GoToMeeting events from medical waiting rooms and took business calls from parking lots.

Nonetheless, business revenue eventually slumped, as it became harder to recruit new clients. She now figures that she will need to spend the next three years rebuilding the business. She also spent a good portion of her savings and retirement funds while caring for her mother.

“It was a rude awakening,” said Ms. Baird, who lives in Fort Atkinson, Wis., and is thankful she was there when her mother died about a year ago. “I’m just now starting to recover.”

Thomas C. West, a partner in the investment advisory firm SEIA, said caregivers can become so overwhelmed that they neglect basic financial responsibilities, like filing their taxes, contributing money to retirement accounts and the like.

He argues that society needs to come up with a way for caregivers to be paid for their work. “You can measure the impact of caregiving on not working professionally,” he said.

Mr. Donham has not remarried since his wife died. He has taken on a role as an advocate for the Alzheimer’s Association, pushing for increased funding for research and greater attention to the needs of Alzheimer families. “It takes people standing up,” he said.